Michael Emerson on Race, ‘People Cities,' and the Potential of North Park

A conversation with the University’s new provost

CHICAGO (August 20, 2015) — Dr. Michael O. Emerson, ���ϳԹ�’s new provost, moved around a lot growing up. He was born up the road from North Park in Evanston, Ill., and spent time in Detroit, all before his family settled in Minneapolis. And like most kids, he was unsure of what he wanted to do with his life.

“I graduated high school and moved to Los Angeles because I had seen it on TV, knew that it’s warm there, and thought, ‘Well, if I can’t find a job, I can at least sleep outside and I won’t die.’”

His candor and light-hearted retelling of his origin story are a far cry from what he would become, a renowned scholar and thought leader on race, religion, and urban sociology. It was a long journey, with some parts deliberate and others caused by circumstance.

After his brief stint in California, Emerson made his way to Chicago and Loyola University. He thought he’d become a banker, and chose Chicago because of its energy and the excitement he found riding the 'L' train around town.

He also rode the train to a class at the downtown campus, and the education he received as part of that helped set him on his future trajectory.

“That experience fundamentally changed me,” Emerson says. “I got off the train for class and I could see the housing projects, Cabrini Green, which were notorious. And you walk a few blocks and there’s the Gold Coast, and all the prosperity associated with it. You just couldn’t have a more dramatic contrast so close together. I had no idea how this had happened and why you’d see people of different color in these two places. I kept asking myself why, and that started my journey to what I ended up doing.”

He switched his major from psychology and statistics to sociology, and after graduation, immediately entered graduate school at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. That began a long teaching career, with faculty appointments at the University of Notre Dame, Bethel University, St. John’s University, and most recently, Rice University.

Emerson’s scholarship focuses on the urban context. He was the head of the International Global Cities Program, charged with creating a strategic global network of researchers, institutes, and programs. He was founding director of the Center on Race, Religion, and Urban Life, and the Kinder Institute for Urban Research, and also developed and directed Rice’s Community Bridges Program, integrating service learning, course instruction, and community development in Houston. In addition, he was founding associate editor of Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, a journal of the American Sociological Association.

Emerson began his appointment at ���ϳԹ� in July, drawn to the University’s Christian, urban, and intercultural values. He is also a member of the , a denomination he says

Before the start of the 2015–2016 academic year, Emerson sat down for a conversation about his research and North Park’s potential in the world.

North Park: You’ve been at ���ϳԹ� less than two months. What’s your impression so far?

Michael O. Emerson: We have a collection of really hard working people. They do a lot with what they have, and I’ve been really impressed. So far I have talked one-on-one with 63 faculty members, all of the deans, and various people around campus. So I am very, very impressed with people’s dedication to what they’re doing.

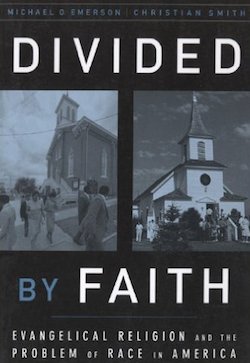

NP: One of your books, , received acclaim in academic and church communities. It discusses the role of evangelicals in preserving America's racial chasm. It’s been 15 years since it was first published. Given the prevalence of race in the news with events in Ferguson and Baltimore, what’s changed since the book came out?

Emerson: In the last 15 years there has been a dramatic shift in the Christian world when it comes to talking about issues of race. And there has been a movement toward having multiracial congregations. We have failed many times, but there’s more focused activity around it. Conversations around questions such as, If we’re segregated, how can we desegregate? If we have inequality, what can we do about it? If there’s injustice, how can we address it?

At the same time, there’s another book that came out a few years back called by Michelle Alexander. It showed how we have re-institutionalized the past, but we do it through the prison system. Once you’re in prison, you’re a second-class citizen for most of the rest of your life and there are things you simply cannot do. You can’t access government housing, you can’t get money to go to college, and the list goes on and on. I think that book raised awareness that there’s injustice in the criminal justice system itself, and people then had a way to name it.

What is now happening around the country, what we keep seeing on TV is people saying “No.” This isn’t some event that happened just because somebody misbehaved, it’s part of this bigger system, and we’re going to say “No more.”

NP: Are there examples of how churches have responded in new ways?

Emerson: We just had another tragedy happen in Cincinnati involving an unarmed black man. There has been a very strong movement in Cincinnati in recent years of starting to worship together, of white pastors who have formed relationships with black pastors and are part of their organizations. When this event happened, instead of just black pastors standing in protest over the death of a young black man, you immediately had white pastors standing there too. Not taking over, because they’ve learned that’s not what you do. But being there in support. And they have actually developed principals: You must act right away, you must do it together, and it has to be clear who speaks and who doesn’t speak. That didn’t happen much 15 years ago. People have been working at it so that when events like this make national news, there’s a set response.

NP: You followed up Divided by Faith with another book, . The first attempts to diagnose the issues, while the second argues that multiracial congregations can be an answer to the problem of race. Taking a step back, as an academic, is it ever enough to just diagnose a problem? Do you always have to propose solutions?

Emerson: At first I thought it was enough to just diagnose a problem, but my own pastor at the time told me something that really impacted me. He said, “I just ate up your book. I was reading it late into the night. I was lying in my bed and I got to the last page and I finished . . . and then I threw the book across the room.” He said I didn’t tell him what to do now. I heard many stories like that. People who said we helped them understand the problem, and they wanted to do something about it, but didn’t know where to start.

Yes, sometimes it is enough to just diagnose an issue. There are great strides we need to make in that area. Although personally and in my own field of sociology, I would say we’ve spent a hundred years diagnosing the problems, but the next hundred years of the field are going to be about how we can use our research methods and tools to suggest how things might improve. And also to test those suggestions to see if they work.

NP: Chicago is an important place for understanding race in America. Given our campus location here, what potential does North Park have to influence issues of race in a positive direction?

Emerson: I told the faculty when I interviewed here that I think that ���ϳԹ� can be the next great American university. We have a desperate need for more great American universities. We have a lot of universities, but many of them are doing pretty much the same thing. It’s a standard set of secular training and when it is done, you move on and you get a job. We have an opportunity here because of our location, because of our history, and because of our mission. We can address major issues of our time.

We are now a world of urban people and we have never been that before. For the first time people don’t access cities and experience them and then go back somewhere else. Increasingly, people spend their entire life in cities and across generations, and they access the countryside or other rural places as tourists. But their life is in cities. We haven’t yet figured out how to design cities as places where people will spend all of their lives across generations. To this point, cities have been designed as places to come and make money, be entertained, and move on. When we look back we’re going to realize that this was a period when we finally, as humans, figured out how to do cities for human beings themselves.

That is one of the roles that I can envision that ���ϳԹ� will have. Collectively, across all of our disciplines, we can work on creating a better Chicago and a better urban life for the people that are pouring into cities across the world.

NP: You spent the last year living and studying in Copenhagen, Denmark. What was that like?

Emerson: I couldn’t have been more stunned. I thought, "I study cities, I know how cities work." And things kept happening that seemed unbelievable. I’ll give you a couple of examples: We hadn’t been there more than two weeks and we got a letter in the mail from the city government of Copenhagen and it said, “In honor of the support of raising your family, we’ll be depositing money into your bank account each month.” And they did! Not to mention the free healthcare and the free education. For instance, you can be 28 and in medical school and you’re getting paid for that. And you’re getting subsidized housing by the city, you’re getting a stipend on top of that for living expenses. I couldn’t understand what was going on. So that’s really the focus of a new book I’m working on.

With but a few exceptions, American cities are what I call “market cities.” They are cities designed to make money and increase regional wealth. Such cities see themselves as existing to recruit jobs, lure big businesses, and grow. That combination, in such a view, makes for a great city. People then will have good jobs and increase their wealth as they wish.

In a place like Copenhagen, they don’t think like that at all. That’s not what a city is about. A city is about producing the best quality of life possible for the entirety of your citizens. So they may think about recruiting businesses if that helps contribute to that, but it’s never their main goal. They’re thinking about how the city can be used as a vehicle to increase the quality of life for its citizens, as a tool to solve human issues like climate change, as a place to be sustainable and promote healthy people. For instance, research shows that people are a lot healthier if they commute to work on a bike instead of riding in a car. So Copenhagen spends major amounts of time, money, and other resources creating a city that encourages its citizens to choose biking rather than driving. They have been amazingly successful. Clearly, they have a fundamentally different approach to city building.

NP: What are the “people cities” in the United States?

Emerson: Portland is one that stands out, as does a place like Minneapolis. My colleague and I developed a one-to-five continuum to classify cities around the world from “strongly market city” to “strong people city.” We have no strong people cities in the U.S., just a few of what we call “lean toward people cities.” We have, though, built a lot of strong market cities.

We classify Chicago as a “lean-toward-market city” because though its dominative motif remains market growth, it’s trying to do some things that are people-focused. It develops wonderful parks. It’s trying to be the bike capital of the U.S. Currently, according to all research and experience, the city is doing their bike lanes incorrectly. But the city is trying. It will get there eventually.

NP: What’s wrong with Chicago’s bike lanes?

Emerson: The current bike lanes put bikers at risk rather than protecting them, leading to dangerous hazards. This would not be tolerated in a place like Copenhagen. Chicago is still “cars-first” but attempting to make allowances for bikes. In the U.S., we typically ask, “How can bikes share the road with cars?” That’s the wrong question. Research is clear: Cars and bikes cannot share space. Cars always win. The error in our current Chicago and U.S. city design is that we have a lane of parked cars, then we paint a strip that says, that’s the bike lane, and then we have moving cars. To be frank, such a design invites death—vehicles must always and continually move across the bike lane to park or reenter moving traffic, constantly putting the biker in harm's way.

The simple solution is to switch the parked-cars lane and the bike lane. By doing so, you create a protective barrier for the bikers and you eliminate cars pulling across the bike lane to park or go.

NP: Shifting topics a bit, we talked about ���ϳԹ�’s identity as an urban institution. What about its identity as a Christian university? What is the role of a Christian university in academia today?

Emerson: We have to begin by asking why Christian universities were founded, and the historical progression they often undergo. Typically a group of people at some point say something like, “Oh, our current universities are really secular. We need to create a place where our students can integrate faith and learning. So we’re going to create a school focused on Christianity.” What then typically happens over the course of 100 years or so—and it happens over and over and over again—is that as the university becomes more successful and attracts more people, pressure mounts to pull back on the Christian aspect of the university. This happens for all sorts of interconnected reasons.

The challenge is how do you, as a university, keep that faith commitment to actually create the better world that you say you want? I think that’s where North Park is situated perfectly. If we’re in this time of trying to figure out how to do new urban life together, you can’t do that without thinking about the great questions behind such a process. What does it mean, life together? What is life for? Why do we exist? We need some sort of guide and direction for the sacrifices it takes to do things that make it possible to make better lives. We need faith and deep, principled motivation.

One of my frustrations when I was in a secular university was having to stop short of talking about why we might want to do these things or asking the underlying questions. Many students, faith commitment or not, think we should have a better world. We have to treat people right, they say. Where does that come from? And when push comes to shove and you can make a lot of money by not treating people right, what are you actually going do in the end?

We need to have that discussion. Humans can’t operate without some sort of moral compass. So let’s talk about that moral compass. At a Christian university, we don’t have to ignore it.

NP: To ask a more personal question, how has your transition to Chicago been? Have you settled in a neighborhood?

Emerson: As a family we were looking for a diverse neighborhood close enough to walk and bike to North Park. We also wanted to be within walking distance of the 'L' train. We found all of this just six blocks south of campus. Chicago, to me, is the greatest American city bar none. There are all sorts of reasons why. Compared to the livability of many European cities, it has a ways to go. But it can get there. The American way of understanding cities is fairly limited, as we talked about. There’s improvements that can be done, but that’ll be the fun part.

NP: What makes Chicago the greatest American city?

Emerson: It’s the incredible foresight that doesn’t happen in most cities. It’s the one that years ago said we’re going to take our most valuable land, the lakefront, and keep it for the people. The ordinance that said there are no commercial buildings to be built east of Lake Shore Drive. That’s incredible. I don’t know how that happened. I’ve read lots of things about it, but I still don’t understand how the business leaders of the time and the political leaders agreed to do that. And what a difference that has made.

Use @npunews to . Learn more .