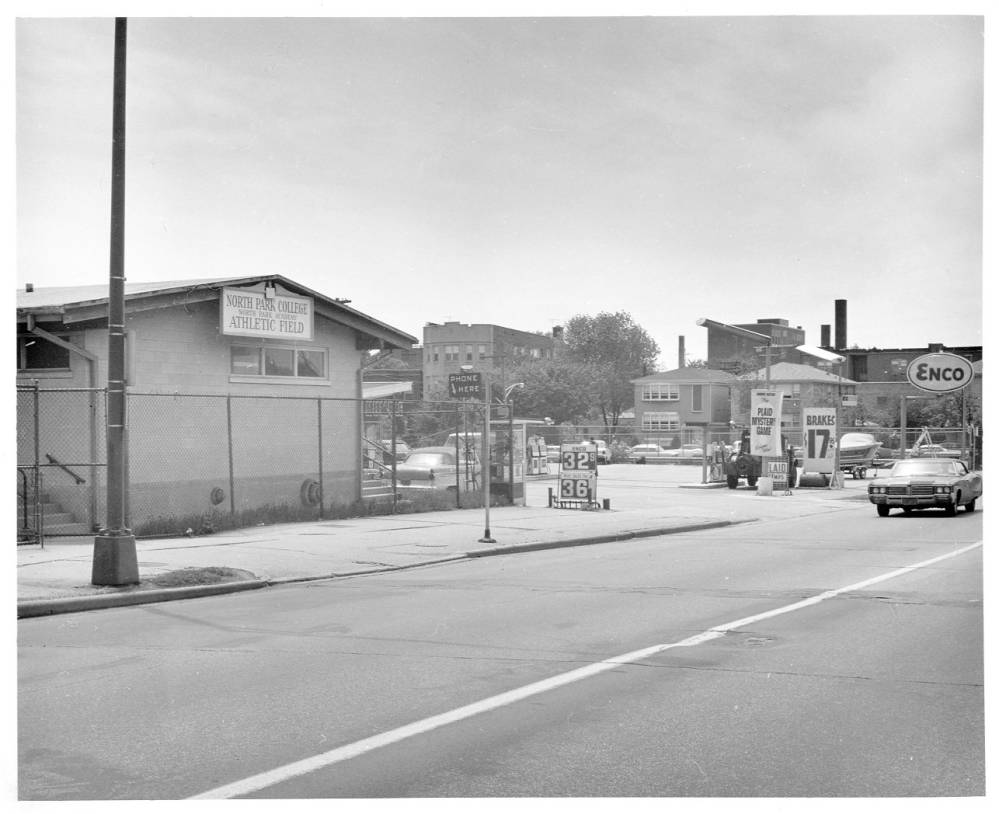

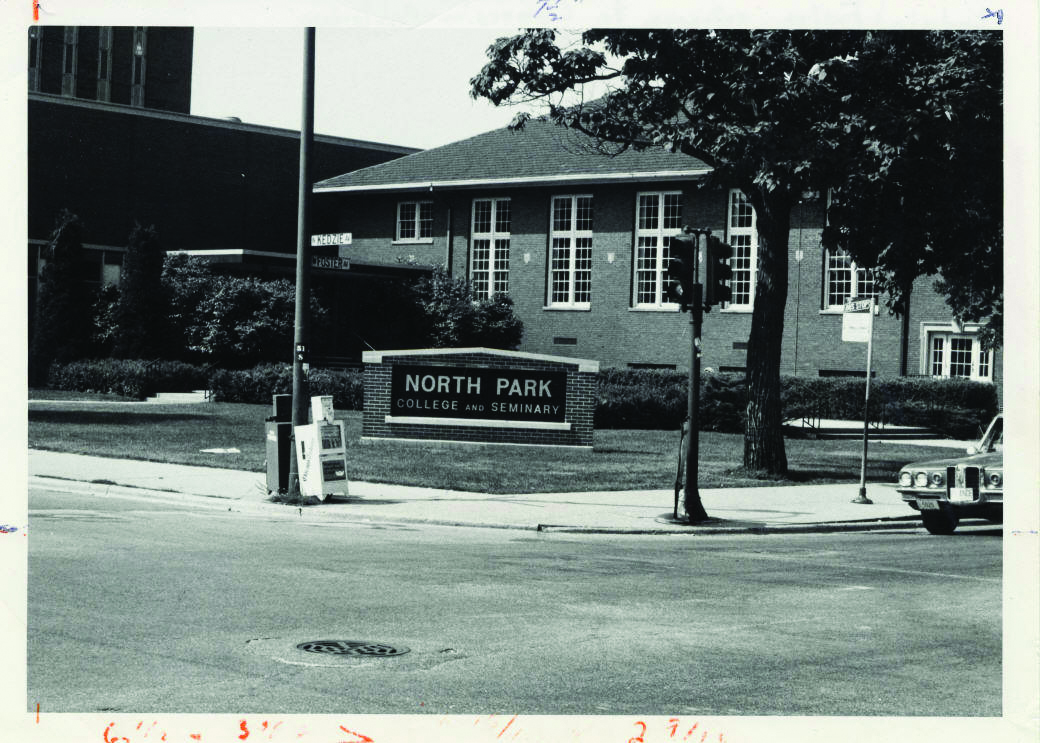

More than 40 years ago, North Park chose to stay in the city, a decision that helped define its identity and mission.

By Ellen Almer BA ’94

While the decades-old choice to keep North Park’s campus in Chicago rather than move to the far suburbs seems like a no-brainer today, the actual decision-making process, said those who remember it, was fraught with tension and drama.

The decision came in 1980, in North Park’s gym, at the Evangelical Covenant Church’s (ECC) annual meeting, where then-President Milton Engebretson MDiv ’54 fretted behind the stage’s closed curtain.

G. Timothy Johnson AA ’56, MDiv ’63, who led the six-person task force charged with recommending whether or not to change the location of the school, remembered how nervous Engebretson was. “He was pacing back and forth.”

He needn’t have worried. Following Johnson’s presentation, the ECC delegates voted overwhelmingly to accept the panel’s recommendation to remain in Chicago.

“I don’t remember any debate or controversy,” Johnson said, adding that members of the task force were mainly relieved because the decision, for them at least, had never been a foregone conclusion.

CONTEMPLATING CHANGE

Just a year before, Dean Robert Sandin recommended that şÚÁĎłÔąĎ stop all capital improvements on its Chicago campus and consider moving to the suburbs.

“We happen to be located in the city of Chicago, and this location has some influence on our constituency, our programs and our lifestyle,” he wrote at the time. “Yet our location does not define our reason for being. On the contrary, for the last 20 years (if not longer), we have really done very little to effectively adapt our programs to the needs of the urban environment.”

He argued the school’s mission was at odds with the location, and the buildings required by the year 2025 would not fit on North Park’s current 20-acre campus.

Arthur A.R. Nelson A ’52, MDiv ’60 interim president of North Park at the time, acknowledged that the school was struggling with lower enrollment and aging facilities.

“We were beginning to do better on admissions, but we were in a bad position,” Nelson recalled. “Some constituents were worried about investing in a college where crime was bad,” Nelson added, a fear he believed was overblown.

In fact, the areas around North Park were beginning to be shored up by a new wave of Eastern European and Asian immigrant populations who brought economic stability to the area, especially in the Albany Park neigh- borhood that bordered the south end of campus.

But when A. Harold Anderson (Anderson Chapel’s namesake donor) graciously offered 100 acres in Grayslake for a new campus, North Park officials were intrigued.

“We really thought about our place in Chicago…we had to ask ourselves if we were doing this for some reason other than [our] mission.” —Arthur A. R. Nelson

STEEP COSTS, STUDENT OPPOSITION

The new campus would have to be built from scratch, officials deter- mined, with all-new facilities. The price was pegged at $37.5 million. Conversely, staying in Chicago would require a handful of new facilities and a badly needed renovation of Old Main for $11.5 million. Although the cost difference was stark, the Johnson-led task force persevered.

“Many Chicago-area people were enthused about it for obvious reasons,” Johnson said. “The idea of a brand-new campus out in the suburbs. So, we felt the need to take the idea seriously.”

As part of the process, the task force, which included North Park stalwarts Zenos Hawkinson A ’41, AS ’43 and Bill Fredrickson A ’34, AA ’36, surveyed students, faculty, staff, and students. The reactions were swift and strong. Hundreds of students signed a petition against relocating, saying: “We can think of no academic discipline that would benefit leaving Chicago.”

“Put the college anywhere else, and it would not be North Park,” said the editorial board of the College News.

“We really thought about our place in Chicago,” Nelson said. “To leave this city is the biggest mistake we could make if we believed in our mission to expand peoples’ intellectual life and make it as expansive as their religious life. We had to ask ourselves if we were doing this for some reason other than that mission.”

Donn Engebretson A ’69, BA ’73, MDiv ’78, Milton’s son and a current resident of the North Park neighborhood, noted that şÚÁĎłÔąĎ was one of the few small Christian schools to remain in a major metropolitan city during a period of widespread relocation.

“Back in the 70s and 80s, the Christian colleges that moved to the suburbs thought they were the prescient ones,” Engebretson said. “Today, with the enormous resources of Chicago, there’s no question North Park and its parent denomination were truly the ones with vision and an expansive understanding of mission.”

Michelle Dodson BA ’02, the sem- inary’s Milton B. Engebretson Chair in Evangelism and Justice, agreed, lauding North Park’s leaders for not succumbing to the “white flight” trend.

“I don’t care how big your commit- ment is to diversity; an institution is marked by its physical space,” Dodson said. “If you’re going to move far from a big city, you know you’ll lose the benefits of a diverse student body.”

Staying in the city is a physical com- mitment to North Park’s intercultural distinctive, she said.

“The world is becoming more urban, and even if you’re not going to live in a city, having that perspective of being in a neighborhood where people don’t look like you, getting on a busy city bus, it significantly shapes you.”

Nelson agreed.

“In the end, the task force realized you can’t just reestablish this school in a cornfield.”

“Back in the 70s and 80s, the Christian colleges that moved to the suburbs thought they were the prescient ones. Today, with the enormous resources of Chicago, there’s no question North Park and its parent denomination were truly the ones with vision and an expansive understanding of mission.” —DONN ENGEBRETSON

ENSURING NORTH PARK’S FUTURE

Many, including Johnson and Nelson, believe North Park would not exist today if the campus had moved to the suburbs.

“We decided we can stay here without trading our values,” Nelson said. And if we hadn’t stayed? Nelson isn’t alone in his assessment: “We would’ve closed years ago.”

The city of Chicago, and the North Park neighborhood, were certainly grateful the school remained.

When North Park announced its decision, Nelson received a supportive letter from then-Mayor Jane Byrne, and local newspapers lauded it.

“North Park College bucks the trend toward suburbia,” said a headline from the Chicago Tribune.

An editorial in the June 19, 1980, edition of the Chicago Sun-Times said: “The decision of North Park College and Seminary to remain in Chicago is good news for the city, and not only because of its academic excellence and crack basketball team.”

And then there’s the question of what the North Park neighborhood would look like if the school had left.

Johnson surmises the campus acreage would’ve been sold to a housing developer, while others questioned whether businesses such as Tre Kronor restaurant, the Sweden Shop, and even Starbucks would be anchors of Foster Avenue.

“As a business owner in the area and a neighbor of the university, I was personally pleased when the university renewed its commitment to the neighborhood and the benefits of an in-city education,” said Carmen Rodriguez of the North Park Chamber of Commerce Planning Commission.

Donn Engebretson credited an expansive understanding of mission by the ECC, which is inclusive of people from every race and ethnicity, for the decision to maintain a Chicago base.

“That vision continues to animate North Park and, at its best, the Covenant Church today,” he said.

“Put the college anywhere else, and it would not be North Park.”—COLLEGE NEWS